Faking It

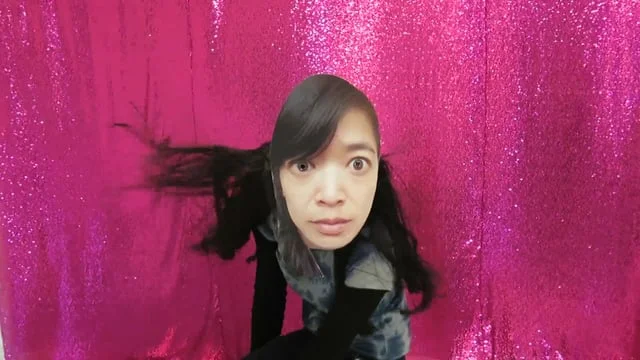

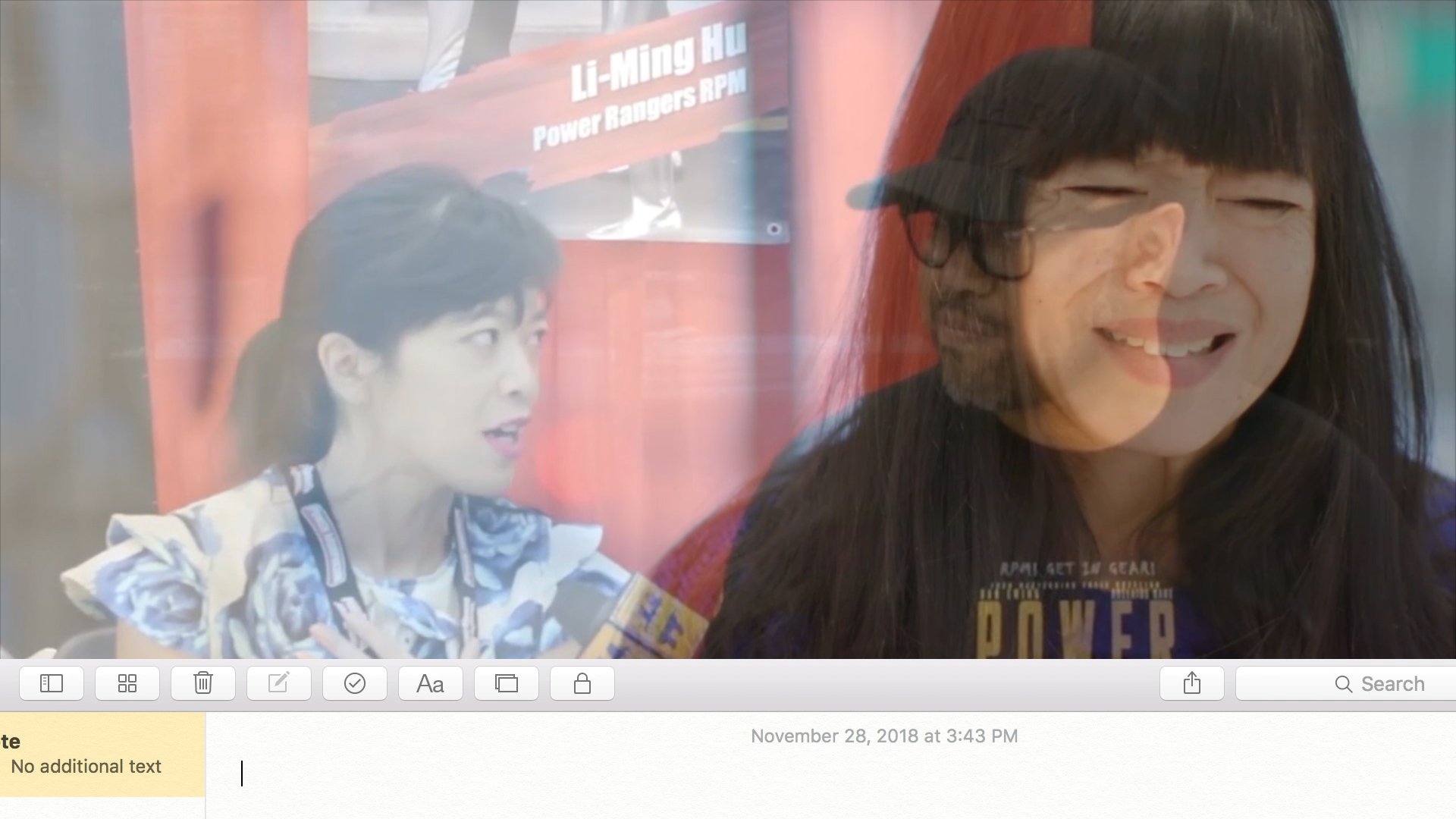

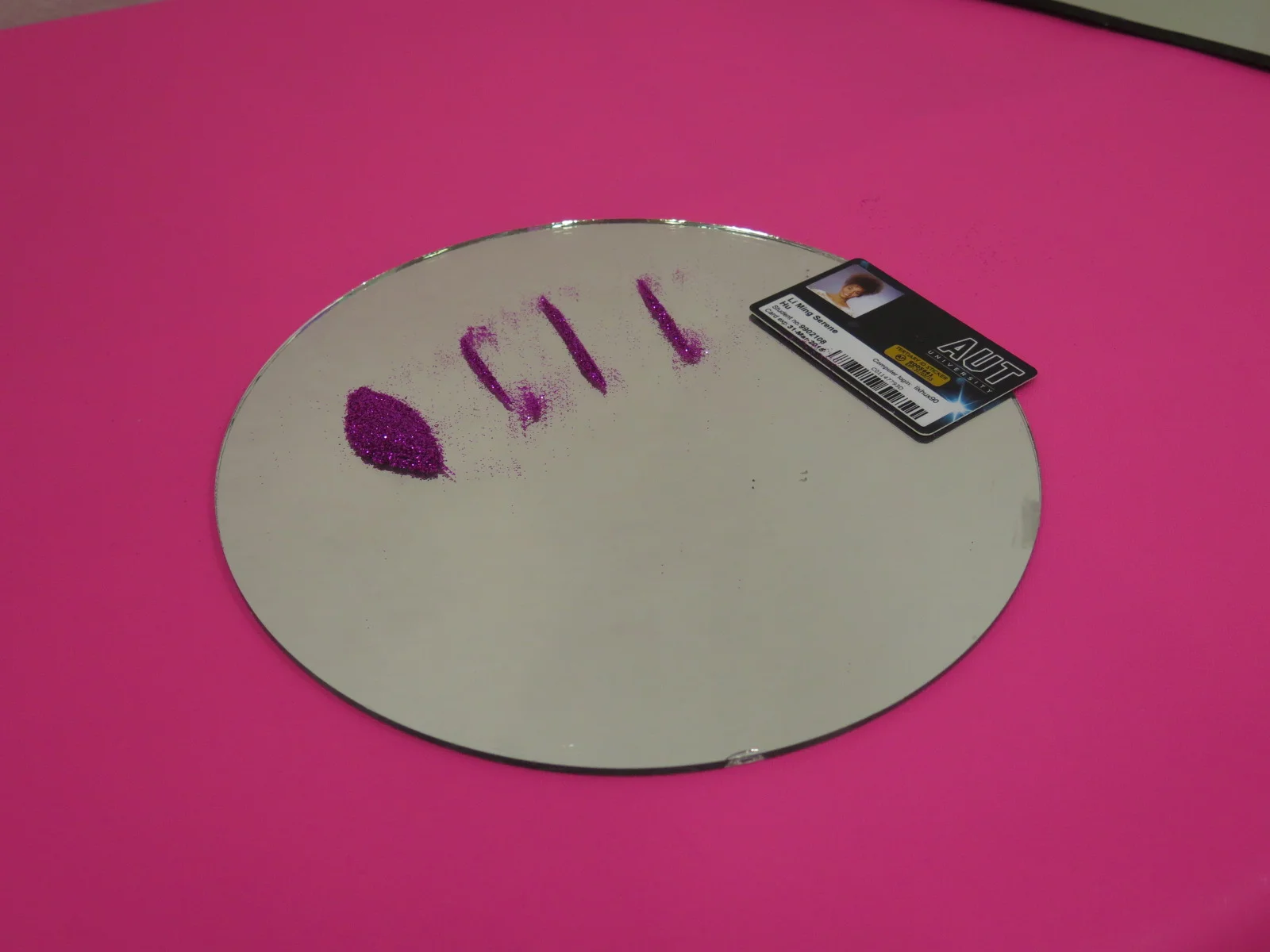

Li-Ming Hu: Deliciously Authentic takes from a tagline of Trident, an Australian brand of Asian foods and condiments popular in grocery stores in her native New Zealand. In a single channel video of the same title, the artist recounts an experience auditioning for a lead role in a series of the brand's advertisements. She further narrates how the client handed down suggestions on how to deliver a more "natural" performance to enhance the desirability of the product. As a hired actress, Hu is not entrusted with deciding what Asia or authenticity means for herself. By the end of the recollection, Hu is dribbling red and white liquids over her mouth in a pornographic innuendo, miming the degrading and dissociative dimensions of becoming what she calls "an optimal vehicle" for consumption.

Hu describes memories such as these with ambivalence, as if being cringeworthy does not quite evidence enough harm to ask for redress. But what makes us insist that Asian exoticization is so minor an offense that it does not warrant a stronger disciplinary reaction? Anne Anlin Cheng locates this wounding as inscribed on both skin and surface in Ornamentalism; her haunting description of Afong Moy, the first "Chinese lady" who performed throughout the 19th century as part of an exhibition across major cities in the United States, attends to the silks and ornaments that make her legitimate. In short, the Asiatic woman was always conjured through the fake, the artificial, "a dream about the inorganic." As one of the longest durational performances inherited through multiple generations, our familiarity with such racist embodiment alone is enough to dull our reaction to it.

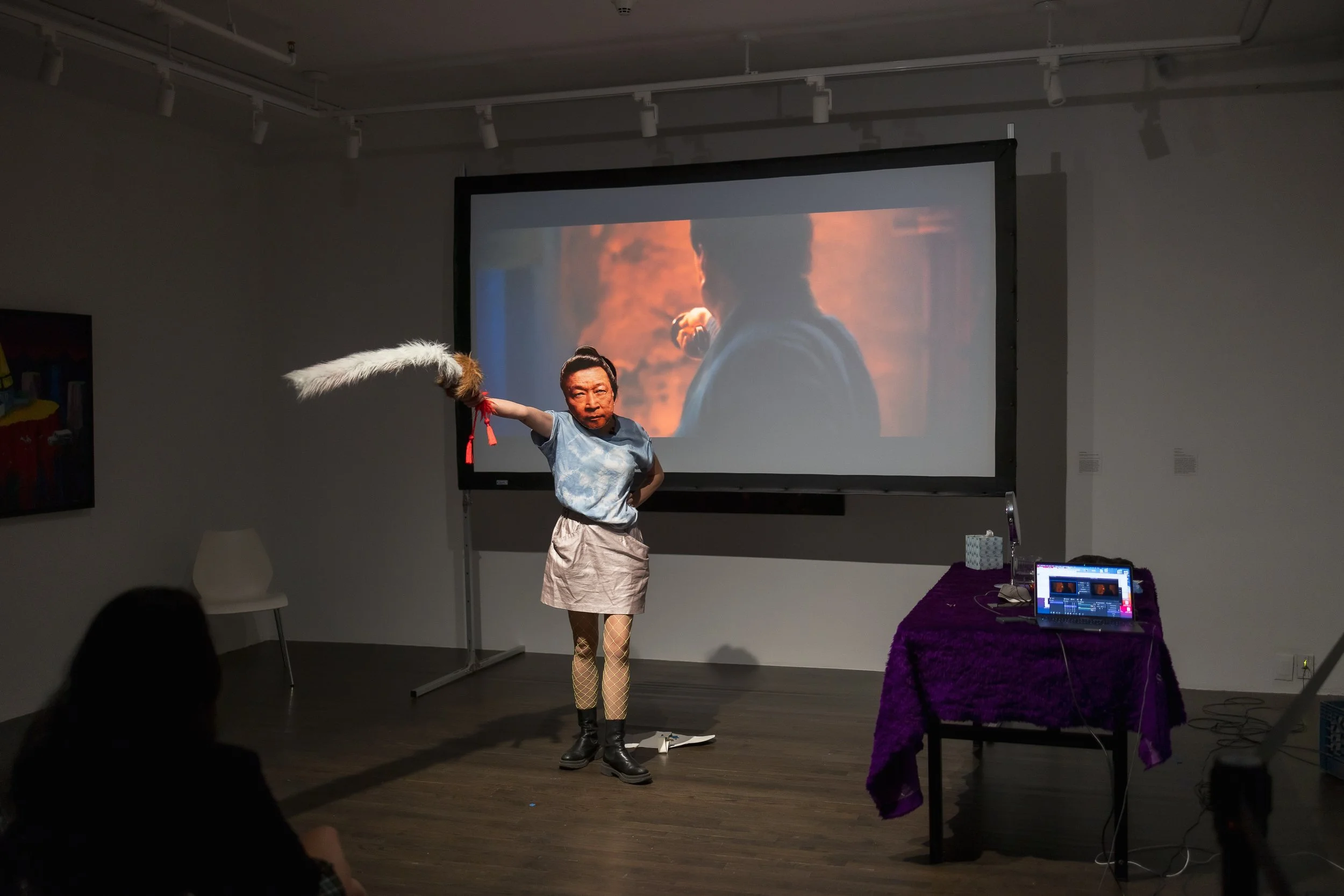

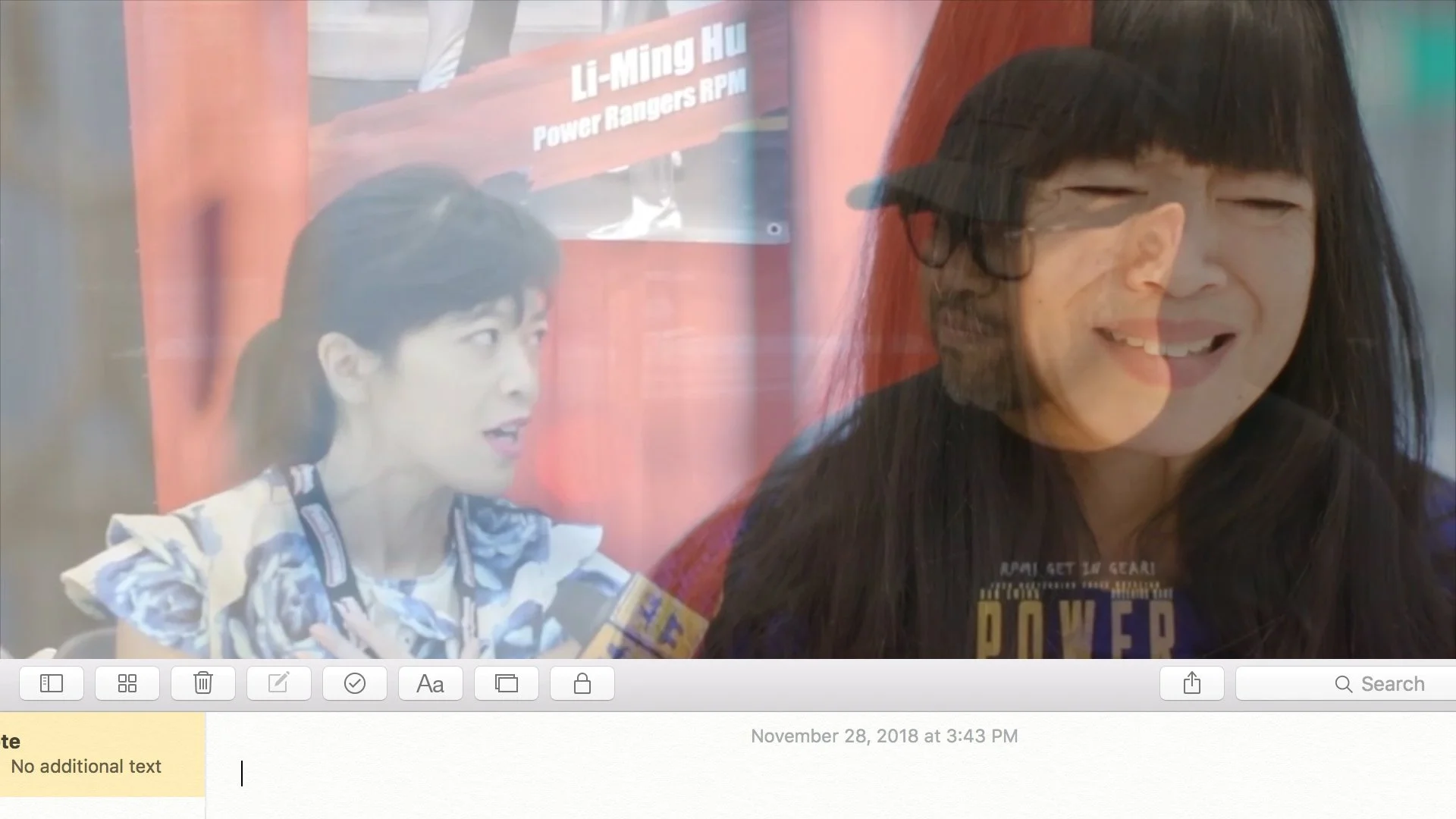

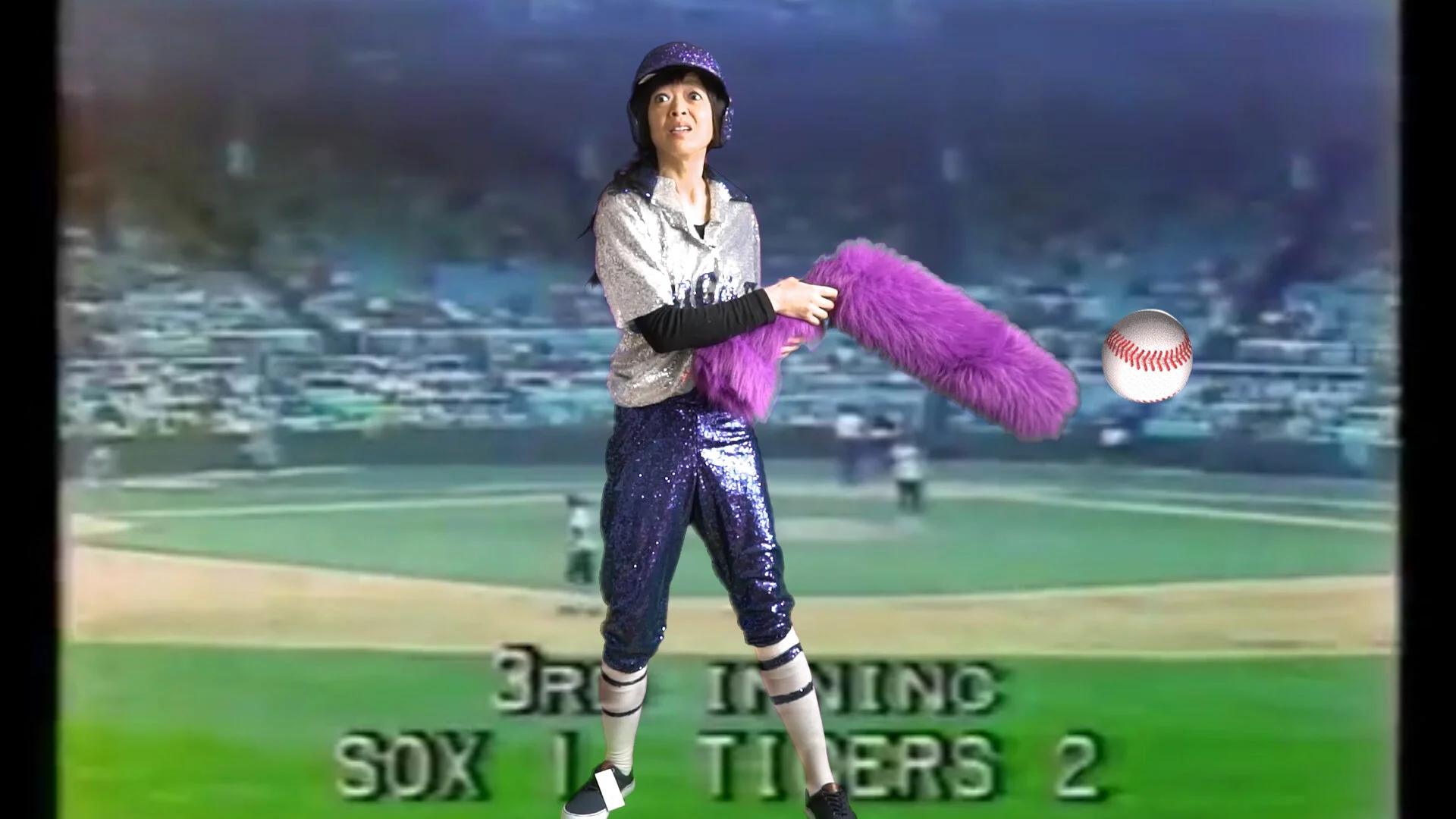

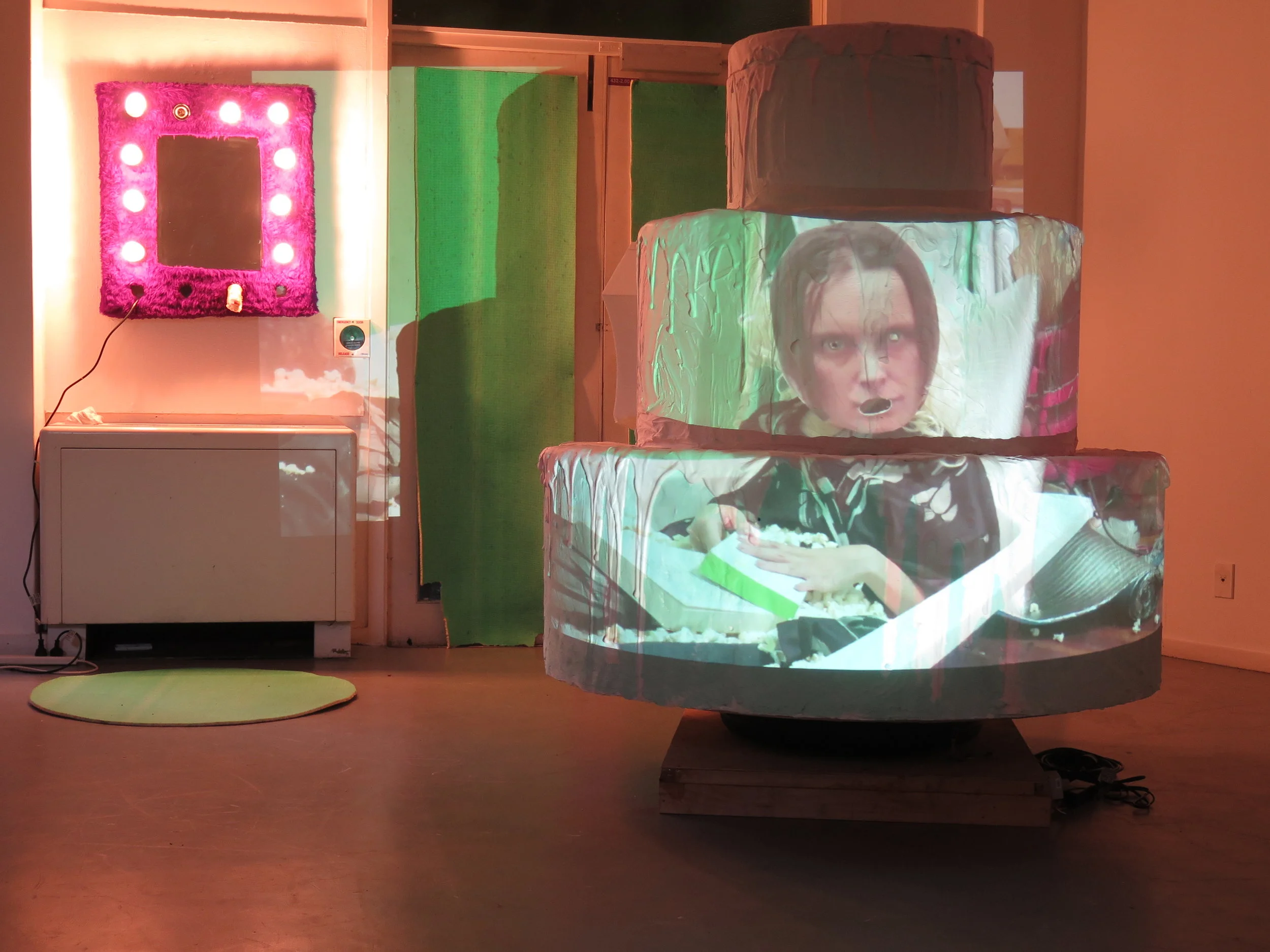

In another video in the style of an online makeup tutorial, Hu dons makeup and wigs to become Jeremy Irons in his role as René Gallimard in David Cronenberg's 1993 film M. Butterfly. Alongside an upbeat backing track, Hu delivers a deadpan account of two instances of yellowface in the theater: Auckland in the 90s for a production of M Butterfly, and the Broadway premiere of the hit musical Miss Saigon. For the second installment, Hu stages a shot-for-shot reenactment of M Butterfly’s concluding scene, in which Gallimard essentially applies yellow face to mourn the loss of a so-called Oriental woman he loved. Hu calls this "double drag" – both roleplaying someone playing another role and dragging between genders and races. (It is notable to mention that M. Butterfly was originally written by Chinese American playwright David Henry Hwang, who was inspired by the opera Madame Butterfly by Italian libretto Giacomo Puccini; Hu thus reenacts a movie directed by a white man who remade a play written by an Asian man written after a white man) Pairing these videos together risks a false symmetry between white face and yellow face, deploying the logic of multiculturalism that isolates cultural consumption away from critiques of power. But Hu shatters this illusion at the end of the video, when she breaks the fourth wall to ask the camera directly, "We can't end like that can we? Not after all we've been through."

Nearby these recorded performances, porcelain figurines spew water from their mouths, their forms based after the famous terracotta warriors at Xi'an, China, infused with the artist's self portrait. The once-delectable Chinese body changes into a state of rejecting what it is fed, but also refusing to be eaten itself–in an attempt to subvert what Kyla Wazana Tompkins has observed to be normalized eating practices within the US empire especially.

Hu's work arrives at a critical time when the prevailing defense against racism is still to assert authenticity as an easy antidote to existing racial order. Hu shows how the demand for authenticity does very little to change the disposability of the Asiatic woman if it was always a critical component of what she was desired for. Historically oppressed minorities are also often offered "opportunities" as a corrective for past injustices. But often the opportunity essentially disguises itself as a traditional role in drag, and Hu challenges the common assumption that the very offer is even a liberatory act.

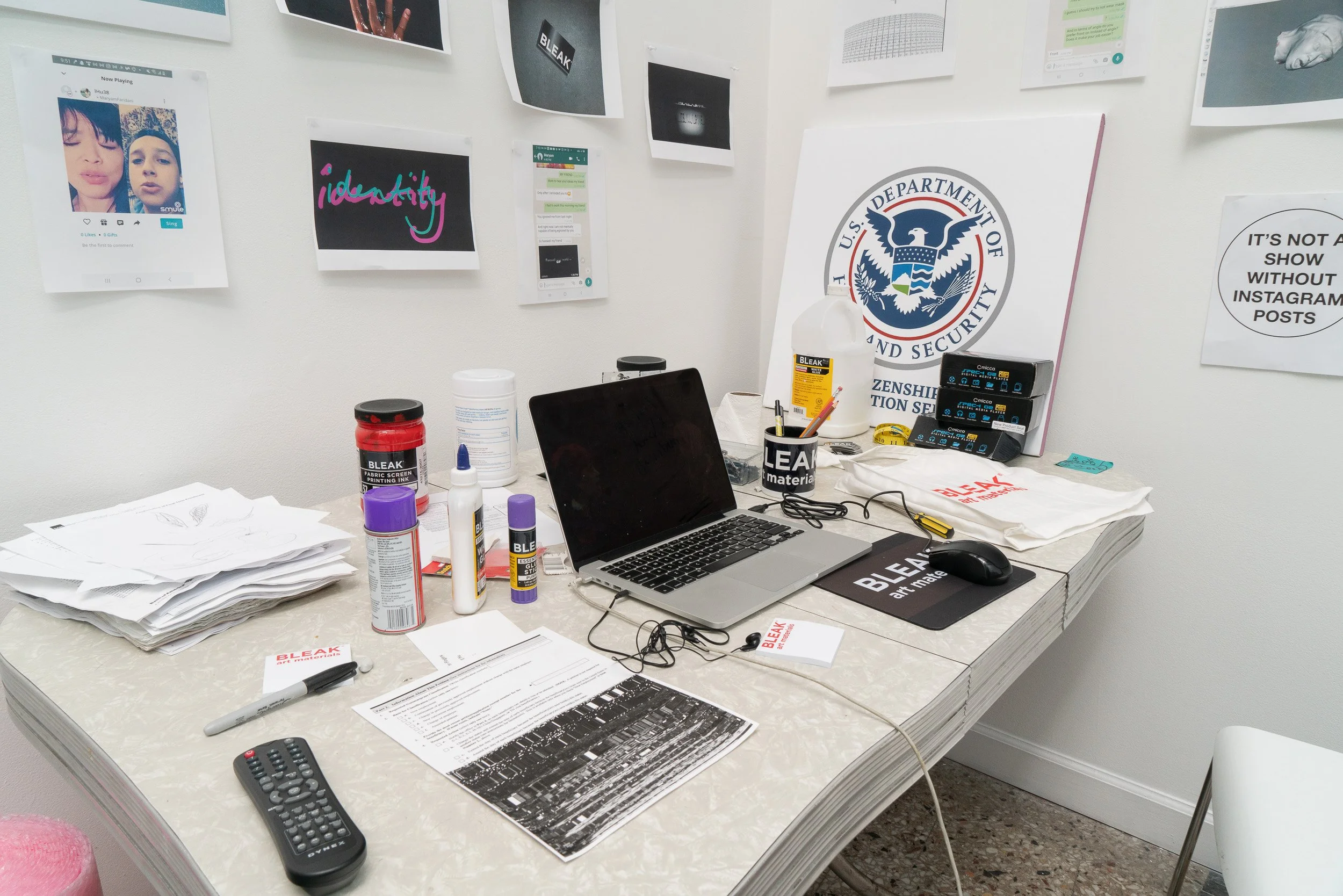

In a humorous, yet earnest interrogation of how commerce shapes the construction of race and gender, Hu also asks a more meta question about how identity-based art functions. What does it mean to be a cultural worker if identity constitutes a raw material to capitalize on? Questions such as these expose the limitations of our current demands, provoking a look beyond existing roles offered to search for an embodiment still more disturbing.

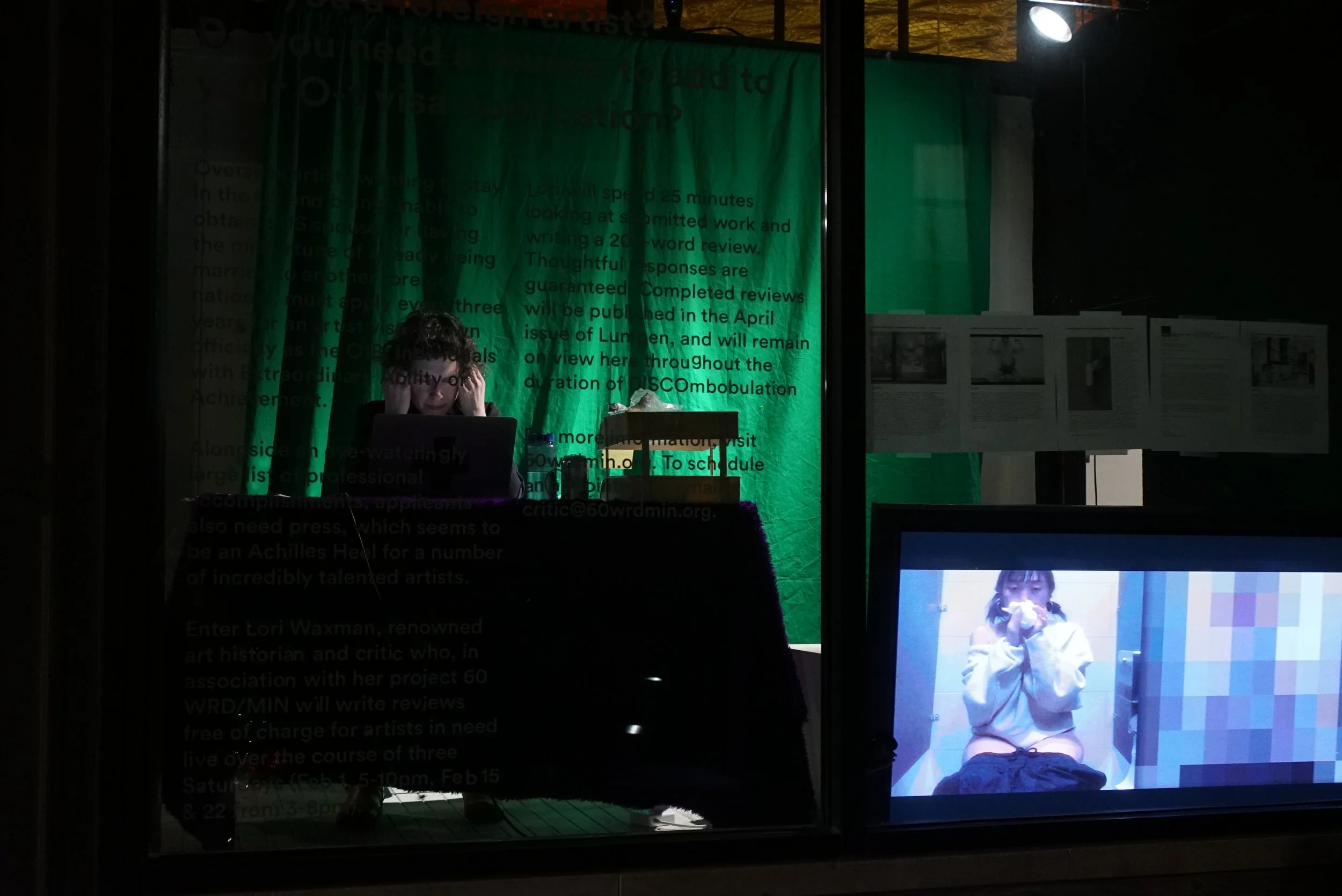

Danielle Wu is a writer and curator based in Brooklyn, New York. She is currently Communications & Database Manager at Asian American Arts Alliance (A4) and was previously a Digital Fellow at Democracy Now! Her reviews have been published in Art in America, Artforum, Frieze Magazine, The Offing, among other publications. Notable curatorial projects include Just Between Us: From the Archives of Arlan Huang with Howie Chen at Pearl River Mart, New York (2023); Water Works at International Studio & Curatorial Program, New York (2022); and Ghost in the Ghost with scholar Anne Anlin Cheng at Tiger Strikes Asteroid, New York (2019).